Sal Mineo was stunning. Hauntingly and uniquely so. His large, brown eyes, sweetly sad and darkly intense, his cleft-chinned handsomeness mixed with an almost cherubic baby beauty that remained child-like longer than he probably would have preferred, were so striking and different that the youth was discovered on the sidewalk. He was with other kids, but Sal stood out. It was 1948 and Sal was outside playing with his sister and friends when a man approached the children. The man asked if the kids would like to be on TV. Sal smarted something back at him and right away – the man saw something a little extra in this kid. He asked to speak to their mother. Later, Sal was approached by a casting agent and likely observed what the other guy observed – his loveliness, yes, but also the child’s charisma and charm, things that pop on stage and in photographs and on television and, wonderfully, writ large, on movie screens.

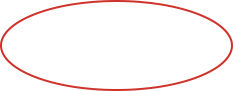

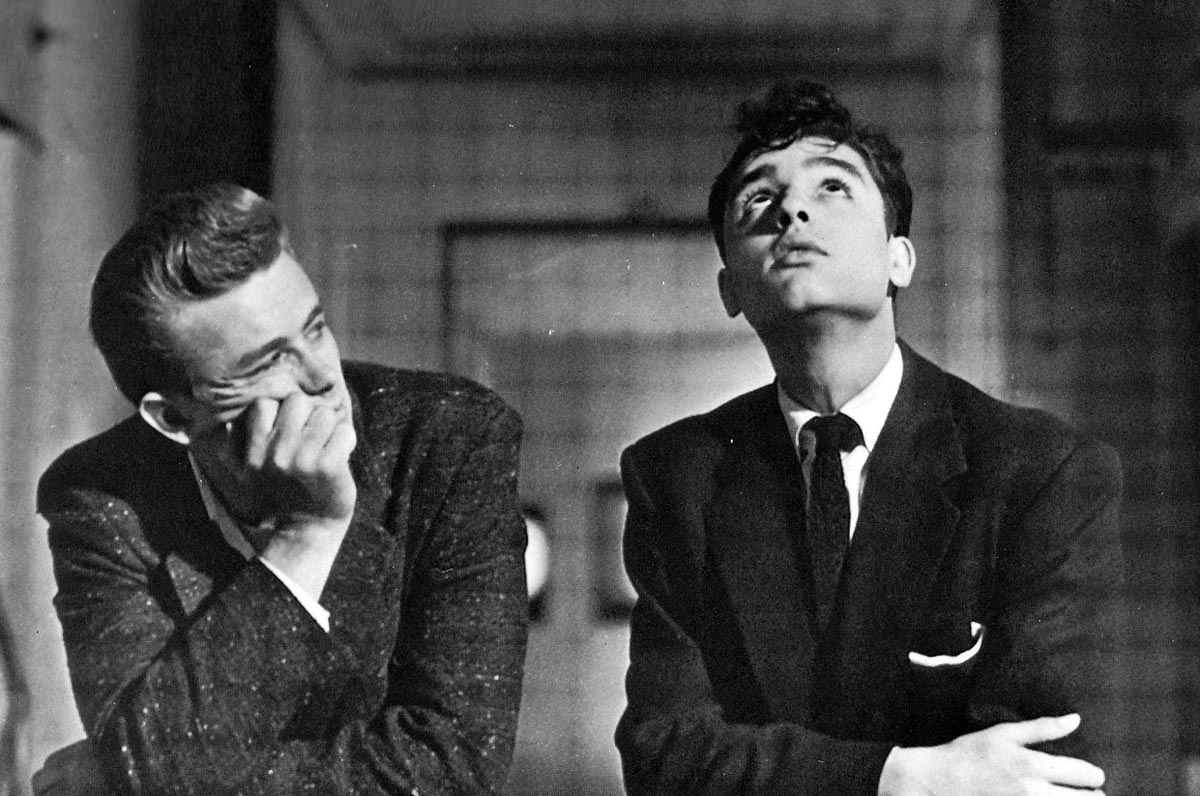

Mineo had that it. It’s not just a matter of attraction; it’s a matter of intrigue, a multifaceted intensity that could move from terrific joy when he breaks out into a laugh with James Dean to bursts of mischievousness, manically slapping the drums as Gene Krupa in Don Weis’ The Gene Krupa Story to the poignancy he shows in just about everything he did. Just look at James Dean looking at Mineo and Mineo looking back at Dean in the mansion scene from Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause (and in particular, the footage of production tests, shot on the sound stages for A Streetcar Named Desire). As much as I adore Natalie Wood in the picture, it’s Dean and Mineo bewitching the viewer with their shared gaze – and not just because Dean was so captivating – but because Mineo was so poignant and mysterious. Take a look at that rehearsal footage – Dean and Mineo playfully horse around until they collapse on the floor, all three leads attentive to Dean, Mineo’s head next to Dean’s as Wood strokes Dean’s hair. Later, Dean drapes his arm around both Natalie and Sal. Dean moves in closer and gives him a little kiss. He hands Sal a cigarette and Mineo cheekily blows smoke on Dean. Jesus. It’s both lovely to look at and sexually charged; their chemistry is undeniable and the attraction so palpable — it’s exciting to see these young men working off each other and also bittersweet. Dean is the bolder of the two, but it’s Mineo’s vulnerability and doe eyes that cast the spell, as if Dean can’t deny what’s right next to him. And he couldn’t. Rebel would not have been the same without Sal Mineo.

The Bronx-born son of a casket maker, the kid who ran from and fought bullies in school, the boy who made himself a little toughie as other boys were calling him a sissy, seemed destined to become a star. From his first stage role – in Tennessee Williams’ The Rose Tattoo where he runs across the stage (his line: “The goat is in the yard!”) – to his last acclaimed role, also on stage, in James Kirkwood Jr.’s P.S. Your Cat Is Dead, where he stars as a crook Vito tied to a kitchen sink, Mineo always remained interesting in spite of how the industry perceived him later in life. To some, he was viewed as frozen in time, forever that teenager, a relic of the 1950s. Of course he absolutely was not that but as often in Hollywood – they don’t like their child stars to grow up, even if they grow up into fascinating actors. Sal’s career struggles makes one angry and disheartened at the industry’s lack of imagination and an uptight homophobic world – Mineo should have been allowed more work and more time. That’s not saying he didn’t continue to create interesting work – he did – from stage to TV to movies. Even in dinner theater, which he disliked, Mineo was by many accounts, impressive. He was daring in an era when such things scandalized squares, he was an artist, ahead of his time, unafraid of controversial subject matter (look up the searing prison-drama play he directed and starred in, opposite young Don Johnson, Fortune and Men’s Eyes), and he lived his life the way he wanted to. When you dive into Mineo’s life and work (I recommend Michael Gregg Michaud’s excellent, essential “Sal Mineo: A Biography,” which aided me greatly in learning more about Mineo), you’re captivated by this very complex, interesting actor and man. You also become upset over what could have been (I thought of all the parts he could have played into the late 70s and on, the directors he could have worked with, the projects he could have directed). You even feel protective. Not that Mineo was pathetic or entirely lost, he was quite strong in fact, but when you know how it’s going to end for Sal . . . you can’t help yourself.

So, it’s touching to know that James Dean took Mineo, under his wing while the other kids on Rebel (excluding Wood, a friend) thought him strange. According to Lawrence Frascella’s “Live Fast, Die Young: The Wild Making of Rebel Without a Cause,” actress Beverly Long said that “most of the actors playing gang members ‘never paid any attention’ to Mineo. ‘He was just young – and weird . . . He was a raging homosexual even in those days. [Sal later stated he was bi-sexual] He was very precious – no fun at all.’ [I doubt he was ‘precious’] Now, however, she admits, ‘We could have been nicer.’” Indeed, Ms. Long. You could have been nicer. Though their alienation likely only deepened his performance as Plato and his bond with Dean. As Frascella continues: “The other cast members may have been somewhat jealous of the attention that Dean paid to Mineo. ‘If anyone was a bit closer to Dean it was Sal Mineo,’ [said Gary Nelson, second assistant director on Rebel]. ‘If he talked to anyone, it was Sal.’” Dean also saw something more in Mineo’s troubled Plato – he was inspired by Sal’s pathos and dramatic pull. Weeping over Plato’s body, Dean was emotional in real life. As detailed in Michaud’s book, Dean “acted as if Sal himself had been shot.” Sal said: “Immediately after the scene, I noticed there was a change in the relationship. He was very protective, and for the whole time he’d never let me out of his sight. He was always there . . . In Plato’s death scene I understood what being loved meant. Now here was the chance for me to feel what it would be like for someone close, someone that I idolized, to be grieving for me. It was an opportunity to experience what kind of grief that would be, what would he be like, what he would sound like, what would he be thinking.” Given what happened to both Dean and Mineo, this statement is doubly haunting and enormously moving.

Rebel co-star Dennis Hopper famously and frequently has been quoted saying a version of this – that Dean’s acting style was in one hand, Marlon Brando saying, “Fuck you!” and in the other hand, Montgomery Clift saying, “Please forgive me.” One could say something similar regarding Mineo, but I’d add another hand – young Peter Lorre saying, “Hide me” – the kid who killed that litter of puppies. That was Sal’s intriguing dimension; something he’d also tap into on stage and in the darker material that interested him. It’s not surprising, then, that he tried to buy the rights to Midnight Cowboy with the intention of playing Ratso Rizzo (he would have been splendid). He yearned to play the role of Perry Smith in Richard Brooks’ adaptation of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. Now, Robert Blake is excellent, I love him in the part, but I can’t get over imagining how great Mineo would have been as Smith, his switchblade kid all grown up, the murderer and Capote muse. He also wanted to play Michael Corleone – with his Sicilian heritage he found himself exactly suited for the story. Obviously that didn’t happen. He was disappointed.

In 1965 Mineo starred in the perfectly seedy, perverse and weirdly beautiful Who Killed Teddy Bear (directed by Joseph Cates), one of his greatest performances and pictures (really, you must see it). The film was considered a low rent trashy curio, now something of a cult classic, though Mineo was given some fine notices (as he should have). He is brilliant in the picture, which lives in a kind of Warholian universe, downtown pulp with a gritty artiness to it – you could imagine the Velvet Underground showing up somewhere or Edie Sedgwick walking into the frame. As the deranged stalker, Mineo is both creepy and disarmingly vulnerable. He’s also gloriously sexualized in a way that manages to not feel exploitative and more artful, more leeringly thoughtful. So much curious attention is paid to his body (an extended work-out scene, a bathing suit pool scene no one forgets and his dance with Juliet Prowse, Mineo wearing tight pants and a shirt that shows off his midriff) that it becomes an independent point of discussion rather than the mere gazing of a beautiful young man. Mineo takes it so much further in this bold performance – you’re thinking about beefcake and violence and sex and then sex messing up a traumatized character’s mind. And you’re even thinking about Mineo himself, the character’s he’s running away from, as if Plato is all grown up, still gorgeous but manlier, and now totally deranged. Take a look at your switchblade kid now. And yet, you still feel for him, you still find a point of identification. There’s something both enigmatic and relatable about Mineo. Nicholas Ray was dead-on with his instinct of casting the teenager in Rebel. In a loaded statement if there ever was one, Ray said of Sal: “I saw this kid in the back who looked like my son except he was prettier.”

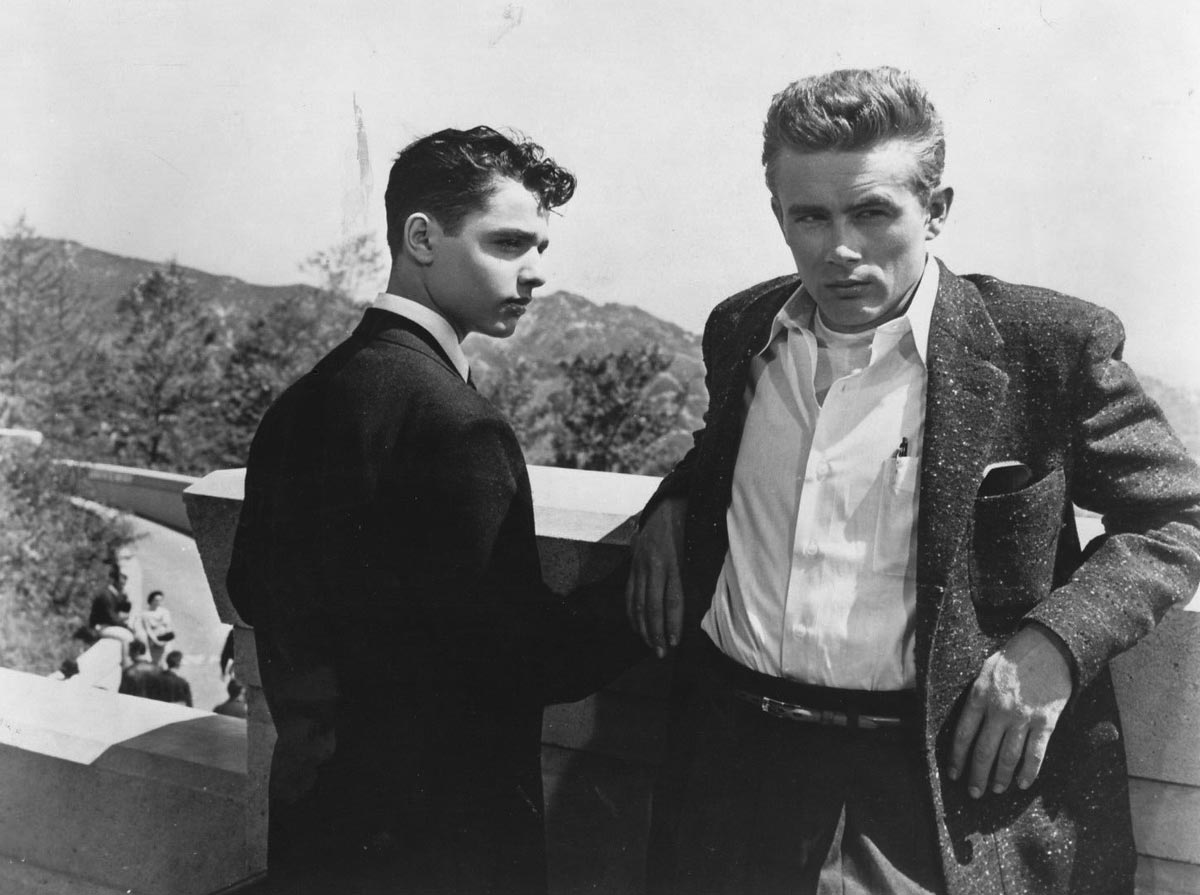

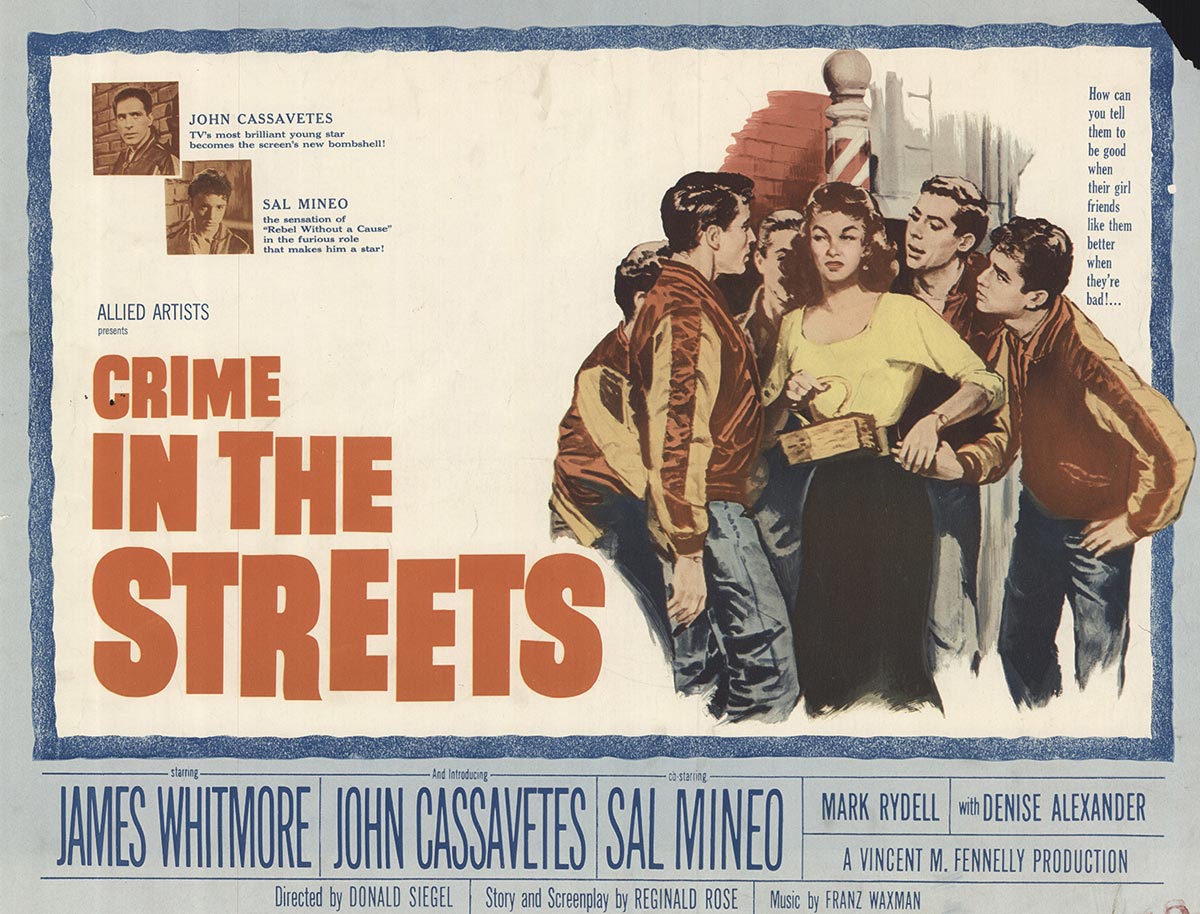

Sal was huge in the 1950s. He had a small, impressive role in George Steven’s Giant, and then he starred in, among others, Lewis R. Foster’s Tonka, Alfred L. Werker’s The Young Don’t Cry, Richard Bartlett’s Rock, Pretty Baby, and in Thomas Carr’s superb Dino as a powerfully tough, wounded juvenile delinquent whose been fucked with way too many times (and who hints at worse). His intense monologues, all flashing eyes and angry, abused and sad, opposite a calm Brian Keith are at times, heartbreaking (this was a reprise of Mineo’s impressive role on the televised Dino, with a wonderful Ralph Meeker in the Brian Keith role, originally played for Studio One). Sal’s youthful draw, the explosion of popularity that, quickly and, by the time of Don Siegel’s outstanding Crime in the Streets would be coined as “Mineo Mania,” would eventually wind up hurting his career. It was tough for Mineo to transition, or to be allowed to. He was deservedly nominated for two supporting actor Academy Awards (Rebel Without a Cause and Otto Preminger’s Exodus), and by 1965, he was in Ronald Neame’s Escape from Zahrain, Ken Annakin, Andrew Marton and Bernhard Wicki’s The Longest Day, John Ford’s Cheyenne Autumn and George Stevens’ The Greatest Story Ever Told. As I mentioned, there was also Who Killed Teddy Bear, which sadly did nothing for future work. But in the ’50s and like Dean, Mineo tapped into the restless hearts of teenage culture, and not just who they crushed on or who they listened to, but their troubles, their delinquency, real or fantasized about, their need to be heard, to be taken seriously, even if by threat or melodrama.

Watching Mineo’s co-star and lead, John Cassavetes’ very serious 18-year-old in Crime in the Streets, we’re actually watching a very serious actor in his late 20s playing a teen. But kids related to that heaviness; that their youthful concerns could be considered important in an adult movie aimed at them. And they loved Mineo. Mineo and the mania was used as a large selling point for an excited teenage audience. Wonderfully acted and interestingly set bound (Crime has a terrific opening rumble sequence) the movie is potently brutal and Cassavetes is really, really believably mean until he breaks and future director Mark Rydell is especially sociopathic (the dialogue coach is credited to Sam Peckinpah). Mineo, however, is the most layered and troubled of the group, giving the most sensitive performance. After all, he was a teenager. He looked like a teenager, even younger than his own years at times, so much that in the picture, the boys call his character “Baby.” In many ways, he’s the most credible cast member, just as he is in a smaller role in Robert Wise’s Somebody Up There Likes Me, in which he plays the more believable New York street youth to Paul Newman’s Rocky Graziano.

But Mineo’s power at playing that kind of kid, and sometimes against men who would be considered the new guard like Cassavetes or Hopper or Newman (all older than him), unfairly relegated the actor to the old guard once he found himself deeper into the 1960s. As Mineo told Boze Hadleigh in 1972: “Hollywood don’t flex its muscle-brain. What you start out as is pretty much how you wind up. I mean, you get typed in the first thing that clicks, then they don’t give you no more fuckin’ chances.” He also said, “When I started in films, I was fifteen, sixteen, and I had this baby face that made me look like a wheat flour dumpling or something. And my fucking name didn’t exactly help.” Watching Mineo in his range of roles, and the pictures featured in the New Beverly’s Sal Mineo series (Giant, Rebel, The Gene Krupa Story, Exodus, Raoul Walsh’s A Private’s Affair, The Young Don’t Cry, Somebody Up There Likes Me, Cheyenne Autumn, Who Killed Teddy Bear, Bernard L. Kowalski’s Krakatoa: East Of Java, Crime in the Streets and Dino), you really see how diverse his talent was. From playing a Native American in Cheyenne Autumn to a singing and dancing private, ex beatnik, and one stealing every scene in A Private’s Affair, to the powerfully bitter Auschwitz survivor, Dov Landau, who becomes militant by joining the Irgun in Exodus, he stands out, with layers and depth and even a self mocking charm (in A Private’s Affair) that wasn’t shown enough (according to everything I read, Mineo had a wicked sense of humor and healthy humor about himself as well).

That Mineo didn’t get no more “fuckin’ chances” is a shame, but he continued to work, directing on stage and putting together provocative projects that never came to fruition (Fallen Dove, written by Mineo and Elliot Mintz, The Wrong People, about young boys in Morocco and their exploitation, McCaffery, about hustlers, which was about set to go until the terrible happened). Looking at and reading about Mineo’s later work, particularly Who Killed Teddy Bear, Fortune and Men’s Eyes and P.S. Your Cat Is Dead, you can see touches of Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey, Hubert Selby Jr., Tennessee Williams and, of course, Midnight Cowboy writer James Leo Herlihy. This is not exactly a guy stuck in the 1950s. This is a kid who grew up fast in the 1950s, who spent a lot of money on his family (a lot) and who wound up losing much more, living in more humble digs, using set pieces and props for furnishings. He did have good ideas. According to Mineo’s friend Eric Williams in Michaud’s biography, Sal even bought the rights to Larry McMurtry’s The Last Picture Show, which he could never get made. He reportedly (not sure if this is exactly how it all went down) handed the book to Peter Bogdanovich (the two befriended each other while Bogdanovich was covering Ford’s Cheyenne Autumn) and quite clearly, that worked out well for Bogdanovich.

When reading Michaud’s biography, I was really struck by Mineo’s final days, before he died too early in life and so terribly in 1976. (I completely understood why James Franco was moved to make an entire film about those hours with his his underrated, impressive, touching Sal starring Val Lerner). Like anyone not anticipating the end, Mineo was working through his day, rehearsing his play and dropping by a nearby mini mart, buying a pack of smokes and a Hostess cupcake before driving home that night. When reading these details, something about that Mineo buying that damn cupcake destroyed me. I thought of the fascinating dualities to Mineo – his extraordinary life and his regular life. This exceptional man who was Rebel’s Plato; who posed nude (face shielded) in Harold Stevenson’s famous painting “The New Adam” (and in 1962); who played frantic drumming Krupa admirably and with style; who did sexy-weirdo-sadness in Teddy Bear; who was a two-time Oscar nominee playing a Manson like figure on an episode of S.W.A.T (and powerfully, do not discount his TV appearances); who was the young man on Shindig! who cut records and discovered other kids who cut records and became stars (namely, Bobby Sherman); who was the young guy on a celebrity panel game show who said women should marry men ten years younger if they wanted to (Lee Marvin thought so too, but for different reasons); the little boy who ran across the stage with the line “The goat is in the yard!” – Mineo was a complex, fascinating man doing something regular – buying junk food like everyone else does – not knowing he’d be walking into a horror that would end his life. That cupcake was almost his last meal. Parking his car in the garage to his West Hollywood apartment on Holloway Drive, a man (later fingered as Lionel Ray Williams in a case that is still confused with misinformation and prejudice, as if Sal was cruising when he was simply walking home) jumped out from the dark and stabbed him. He stabbed him once, but where it counts – in the heart. Mineo died quickly. He was 37-years old.

Mineo had said in interview a year before: “I’m thirty-six now, and I still fantasize. And it’s very bizarre how so much of what’s happened in my life I’ve fantasized way ahead of time as a kid. It jolts me sometimes, how it manifests itself, when it was a seed that I planted as a little kid, y’know? I’m just so terrified that one day I’ll become realistic, and when I do, it’ll be all over. I just won’t be stopped if I want something. It may take years, but it will happen.” He shouldn’t have been stopped. Viva Sal.