“You always play the bad guy on these shows? And they have a fight scene at the end of ‘em? And you lose in the fight? Oooooooh, that’s an old trick…So you got a new guy…You wanna build up his bona fides so you hire a guy from a cancelled show to play the Heavy. Then at the end of the show, when they fight, it’s Hero besting Heavy…Now with another couple of years playing punching bag to every swinging dick new to the network, that’s gonna have a psychological effect on how the audience perceives you…Down goes you, down goes your career as a leading man.” – Marvin Schwarz, producer [Once Upon a Time in Hollywood‘s Al Pacino]

“…I explained to [Quentin Tarantino] that I would be thrilled if he wanted me to do [Jackie Brown], and if he wanted me to play the good guy in this picture it would change my life in several ways – one of which was that I used to be a good guy in my career, but from the time I did The Delta Force, where I played a terrorist, I’ve been a bad guy. I haven’t played a good guy since. And I told him I’d like very much to have a good guy career again…” – Robert Forster, actor

“You only have so many seasons,” Robert Forster muses to co-stars Fred “The Hammer” Williamson and Frank Pesce during recording of the commentary track for William Lustig’s lurid and bone-powderingly brutal 1983 urban vengeance film, Vigilante. The actors sit in the darkened recording studio, eyes shining in the shadows, watching their younger selves on the screen-watching as they play factory workers out for a drink at a bar after a long day’s work, speaking with the wistfulness of older men for whom time and seasons have passed. The older men all take notice when actor Steve James (who would also co-star with Forster in 1986’s The Delta Force) enters the scene as a young cop-Steve James, who died at the age of 41 from cancer. Forster watches the actor on the screen as his co-stars lament James’ early passing. “You only have so many seasons,” he muses to them all. “So make the best you can.”

Trace the arc of nearly any performer’s long career and you’re bound to note high highs, precipitous drops, and all manner of incurvating loop-de-loops through purgatorial paycheck gigs. It’s part of the world – and the life – of a working actor. But for Robert Forster, it was something else, something intrinsic and special and almost legendary – it was part of his mythos: The strong, silent leading man with the impossibly-pursed lips and flat, matter-of-fact Rochester accent whose simmering stoicism literally rode naked into cinema with his debut in John Huston’s Brando/Taylor-starring Reflections in a Golden Eye in 1967 before galvanizing screens further in Haskell Wexler’s early New Hollywood masterpiece Medium Cool two years later…who then began to experience a slowdown in the 1970s, despite the strength and promise of his work (yet even in this slowing ‘70s sigh before the slump, he never gave less than interesting, nuanced, truthful performances)… who then fell into a spiraling ‘80s/’90s odyssey of exploitation actioners and gonzo straight-to-video titles, first as a leading man and then almost solely as a villain, slipping from Hero to Heavy…continuing to mine his craft as best he could for over a decade before a chance encounter with Quentin Tarantino earned him the role of Max Cherry in 1997’s Jackie Brown and put him back on top, on the screens, in the light – as the good guy – where he belonged.

It was a comeback on par with a resurrection, wrenching Forster from basic cable fucksweat fodder like Point of Seduction: Body Chemistry III and into the works of Tarantino, David Lynch, Michel Gondry, Alexander Payne, and Vince Gilligan. And in the weeks after his passing from cancer on October 11th (the same day his final film, El Camino, premiered – ever the pro, Forster worked until the very end), that unbelievable comeback dominated the tributes, obituaries, and conversations that followed (with a few exceptions, such as Kim Morgan’s lyrical, immersive tribute to the entire breadth and scope of his long career). And yes, while that comeback is a critical aspect of Forster’s story, it’s not the only one – and to focus solely on it and its subsequent heyday is to do a disservice to the amazing (and amazingly consistent) work he delivered as a genre journeyman during the period some would consider a nadir.

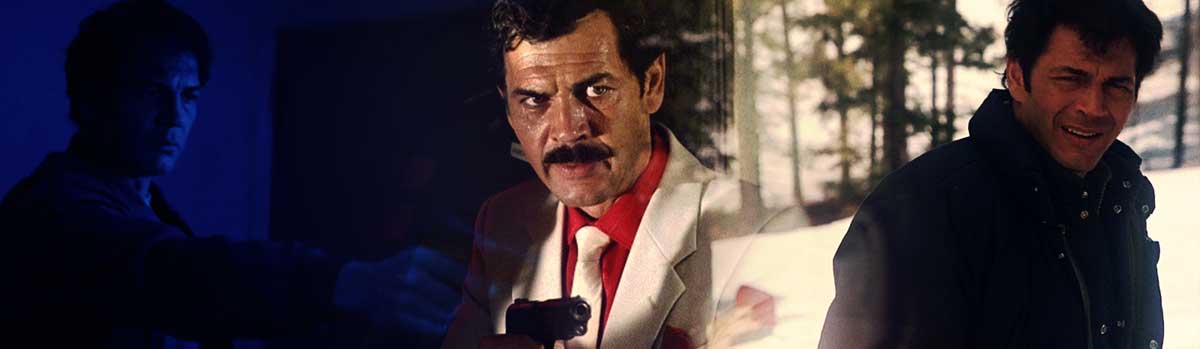

All of which is to say just how special the Robert Forster triple bill of November 20th and 21st is, how artfully arranged it is to convey the full narrative expanse of Forster’s career using the structural vocabulary of three wildly varied exploitation films and his character arcs within them:

As any New Bev devotee knows, one of the deeper, nerdier pleasures offered by the theater is the opportunity to explore how the grouped films on any given night communicate with one another, what they have to say/reveal about the other. And by that metric, perhaps even more so than the fascinating thematic connections between Alligator and Jackie Brown, it could be argued that this triple is the most enthralling of the month-long Forster tributes – using the films from the darkest season of his career, it’s an evening that marks his slide from leading man to cinematic anti-hero (Vigilante), from anti-hero to outright villain (The Delta Force), and finally, with a bit of timeline trickery, from villain back to heroic leading man again (1978’s Avalanche). It’s a two-evening, three-film prism through which the sweep of Forster’s career is represented entirely by his underappreciated season as genre journeyman, a nifty bit of scheduling that succeeds in thematically unifying and strengthening all three of these already entertaining (but each quite different) gems by organizing them as a kind of cinematic biography – these three roles, joined together as one singular nightlong journey, neatly match the path of Forster’s own career from Hero, to Heavy, and finally back to Hero again.

William Lustig’s Vigilante launches the triple bill with an icy, neon-graffiti’d fuckmare of urban vengeance in which decent blue-collar types are pressed into fascistic lynchmob violence not just by the rabidly violent street gangs raping and murdering NYC’s increasingly shellshocked populace, but by the “System” of overworked police, sleaze-slicked defense attorneys (including Lustig alum Joe Spinell in all his hairgreased and pockmarked glory), neutered prosecutors, and lazily dismissive judges who offer no protection as the city continues to sink deep into a blood-gunked quagmire of nihilistic indifference. Less a take on Death Wish than it is a strange and harrowing perfection of the wave of Italian poliziotteschi films that rushed forth in Wish’s wake, Vigilante is Lustig at his most ambitious, crafting a more commercial, mainstream piece of sociopolitical exploitation cinema that still has the raw, roughshod vitality of his own Maniac surging through its bruised and battered veins directly to its blackcharred heart.

Amidst the appalling brutality of the city, the film’s leading man – Forster – is introduced as loving husband and father Eddie Marino in Vigilante’s most (read: only) bucolic sequence, an almost saccharinely sweet scene in which he teaches his son Scott (Dante Joseph) to use a remote control airplane on a fall afternoon while his wife, Vickie (Rutanya Alda), lovingly looks on. Later, a chance intersection with a blank-eyed and dead-souled gang of street thugs leaves Scott shotgunned dead and Vickie beaten into a coma while Eddie is out with friends… and in a final layering of horrors, Eddie himself is jailed for contempt after screaming at the judge who gives the gang’s leader a suspended sentence. Until now, Eddie has resisted joining the vigilante goon squad led by his friend and coworker, Nick (Fred Williamson) – but the bitter irony of his own incarceration is too much. It concretizes the ashen horror of his reality, and the permanent dissolution of his soul. Once free from jail, Eddie becomes the Bronson-esque vigilante of the film’s title, and as the city collapses into damnation around him, so too does Eddie – just as Forster’s career was, at the time, slipping into b-movie doldrums. His display of bitter, coldly unrelenting fury is terrifying to watch – especially following his introduction as a warm family man – and it makes the more extreme plot twists and kinks somehow all believable, especially when Vigilante even allows him to go too far. Using his son’s toy plane’s remote control as a detonator, Eddie goes so far as to bomb those even tangentially connected to his new life of pain. Lustig himself has stated that, as Eddie drives his family’s van past the flaming crater of a remote-control bombing, he’s “now on the road to hell.” His pain has driven him beyond eye-for-an-eye vengeance – he’s a fascist terrorist, lashing out at whatever he deems unjust with murderous, explosive rage. For all its violence and cruelty, the most disturbing thing about Vigilante may be that it knowingly allows its hero to become the bad guy, in a sickening surprise gut-punch that mirrors Forster’s own drop from marquee headliner to wild-eyed villain.

Menahem Golan’s 1986 Cannon Film opus The Delta Force smartly follows Vigilante by introducing Forster’s villainous Lebanese terrorist, Abdul Rafai (yes, really) as the plausible endpoint of Eddie Marino’s own terroristic vengeance, and he begins where Eddie ended. Frenzied and electric in a white linen suit and red shirt, Forster’s Rafai is a rare Cannon villain – three dimensional and human, haunted and smoldering by the pain and loss he has suffered. It is almost as if this is what became of Eddie after being hollowed out by the grief, rage, and hate of Vigilante. And just as it firmly entrenches Forster in villain mode for the evening, so too did The Delta Force trap the actor with a stereotyping he longed to break free from. “First time I ever played the bad guy,” he told The AV Club in 2011. “I didn’t want to do it. I got stuck in bad guys for 13 years after that.”

While The Delta Force was a choice Forster seemed to regret, you’ll be happy to have seen it on the big screen, as it may be the most oddly enthralling film of the evening, if not the entire month. A peculiar and garish merging of a powerful, New Hollywood-ish ‘70s-styled thriller with a typical Cannon-esque Chuck Norris action extravaganza (all of which is lightly peppered with Hollywood disaster movie casting: George Kennedy, Martin Balsam, Shelley Winters, Joey Bishop, and Bo Svenson all pop up as hostages), The Delta Force plays as two films in one. The first hour belongs entirely to Forster as he hijacks a flight from Cairo to New York, barking out typical ‘80s Heavy dialogue about bringing about a “New World Revolutionary Organization” but imbuing the performance with layers of jagged, broken-souled humanity and truth – his Rafai may be the bad guy, but there’s no relish or mustache-twirling to his cruelty, only a sadly believable and desperate drive to reshape the world as something that will no longer wrack his life with pain and ruin. Tense and sweat-soaked (literally: the airplane sequences were filmed during an agonizing summer in Israel with no air-conditioning) as Rafai is forced to contend with – grudgingly bond, even – the lives he’s attempting to destroy, the plane sequence is literally and figuratively the finest hour of Menahem Golan’s directorial career. And while the film’s second hour tends towards typical Norris-y high-kicks and boom-booms (though you also get Lee Marvin and rocket-launching motorcycles – this will kill with a late-night New Bev crowd), Forster still shines, even if Rafai’s position dwindles to essentially a bloodied punching (and remember, kicking!) bag for Norris to use in to assert his dominance over the film, to “build up his bona fides,” to the point that one almost feels sympathy for this evil man, despite what he has done – thanks entirely to Forster’s performance.

“You’re going to have to go to Israel and play the bad guy,” Forster’s agent told him before filming of The Delta Force began, and, as the actor puts it, “I did. And I got away with it. And I got stuck for 13 years. Until Jackie Brown pulled me out of the fire” and back into leading man status. And it’s that famed upswing, that seemingly impossible comeback, which the evening finally represents with 1978’s Avalanche. A Roger Corman-produced attempt to capitalize on the disaster movie craze of the ‘70s (making it a fun chaser to the light disaster elements of The Delta Force’s first hour), the Corey Allen-directed Avalanche positions Forster as a mystery man at first – is he Heavy or is he Hero? – while introducing Rock Hudson’s David Shelby as a ski resort developer looking to rekindle his marriage with ex-wife, Caroline (Mia Farrow), at the site of his newest venture, except that that damn Forster keeps getting in the way – along with massive third-act avalanche of fake snow and stock disaster footage.

While Avalanche may be the weakest of the night’s three films, it’s still a 90-minute slice of breezy New World Pictures fun (that should play like gangbusters on the New Bev’s big screen after midnight with a loosey-goosey crowd), and it is certainly the film that most benefits from the thematic lattice that binds this triple feature together. As the soap opera marriage theatrics (and sad disco dance parties) ensue, we watch as Forster’s mysterious Nick reveals himself to be a person of extreme decency, a matter-of-fact everyman with a good heart and an easy charm about him – i.e., he’s Robert Forster, the one we were reintroduced to with Jackie Brown. The one we remember. The one we love. The one who made the best of what he had – even when he got stuck with some clunker dialogue (“I like you. Just the way you are”). There’s something that just feels right about Robert Forster being our leading man, even in a silly flick like this. And just as the night’s final film shows us Forster emerging from a white hell of frozen terror, by placing Avalanche out of chronological order, so too is the evening’s triple allowing us to see him reemerge from the type of character he was so tired of playing and finally “have a good guy career again,” just as his real-life career did some 20 years later. And in a final thematic resonance, it’s so right to end a triple bill representing the arc of Forster’s career with Avalanche being the film denoting his comeback – for it’s on this film that Forster met and befriended second-unit director Lewis Teague, who would then go on to cast Forster in Alligator, which more than any other may have been the movie that convinced Quentin Tarantino to cast him in the role that forever changed his life. “I’m glad you were here,” Forster in his final scene in Avalanche. “It was important.” Watching this triple, it’s impossible not to feel the same.

~ ~ ~

“You only have so many seasons,” Robert Forster muses to co-stars Fred “The Hammer” Williamson and Frank Pesce during the recording of the commentary track for Vigilante, “so make the best you can.” He says it plainly, with that hard, straight shooter style that marked all of his work and made anything he did or said not just believable, but the truth. The kind of thing that’s so obviously aphoristic, if anyone else said it, you’d roll your eyes. Like that line from Avalanche: “I like you. Just the way you are” – as Kim Morgan notes in her essay, “the line could be so corny, but it’s so sincere and sweet as delivered by Forster.” When he did it, when he said it, we believed him. Whether he was playing an urban vigilante, a snowbound photographer in a love triangle, or even a Middle Eastern terrorist – when he performed it, we believed him. So his co-stars listen when he tells them about the seasons of life, and maybe some of those are seasons in hell…but we know that this season of Forster’s career, this winding journey through genre cinema, was more than just that. It was a season that displayed everything he could (and did) do – from charming leading man to anti-hero pushed too far to out-and-out villain all the way back to the hero again, just like his career. “You only have so many seasons,” he says, knowing that some are freezing winder avalanches, but trusting that they always lead to a spring, and a rebirth, a comeback. And sure that sounds so corny – and it is – but when Robert Forster did it, we believed him.